|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

By Eric Gershon

|

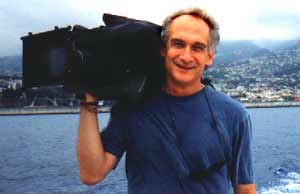

At the end of a red clay road in rural Laos, freelance cameraman Eddie Marritz stood among the milling chickens, goats, and cows, contemplating angles and perspectives. A tributary of the Mekong River flowed behind a cluster of elevated bamboo and straw huts. Beneath each hut several provincial Laotian women sat at looms weaving textiles that, thanks to the Internet, would later sell in Seattle for $500 each. Marritz was there to get the scene on film for a CNBC documentary about money. The job in Laos was, so to speak, just another day at the office for Marritz. In his type of project-based work, travel is a given. Filmmakers document life in pictures, and because life happens everywhere, Marritz goes everywhere. By the time he arrived in Laos, the CNBC project ("A Thousand Years of Money") had already taken him to England and Spain; in between he'd gone to Central America on an unrelated assignment. In every place he goes Marritz meets people and hears their stories. One of the best parts of the job, he says, is "observing what other people's lives are about." The thrill of a varied and itinerant career, however, weighs against the tremendous responsibility that comes with the freelance life. The chief -- the only -- executive of his career, Marritz must, for example, regularly calculate whether an assignment is worth the effort or not. And money isn't always a reliable measurement of worth.

Berlin Story Last summer, PBS producer Helen Whitney left a short message on the answering machine at Marritz' Manhattan apartment. Could he shoot for the PBS program "Frontline" on September 19 and 21? Whitney left no other information -- no subject, no location, no details whatsoever other than the date of the shoot. Nothing. At first Marritz thought he'd probably pass up the job: Although he had recently worked well with Whitney on a "Frontline" project, the dates she was proposing coincided with Marritz' son Ilya's departure for Berlin. Ilya would be away for a year, and Marritz wanted to be free to send him off properly. "My family has had to be very flexible in the past because I've felt I had to take jobs," he says. Marritz missed Ilya's high school graduation because he was shooting a video for the Harvard Business School in the Midwest. ("He was about to go to college and we thought, 'How are we going to pay for this?' so I took the job.") Another time, while his brother was getting married in Seattle, Marritz was darting around Los Angeles in a bulletproof vest filming a documentary about police raids. Marritz especially hates to turn down assignments from people he likes working with -- but experience had taught him where and when to draw the line. Ilya would be away in Europe for at least a year. "I called Helen back in Boston a day later and left a message on her hotel voicemail saying that I didn't think I could do the job," says Marritz. "I wanted to be around for Ilya's departure for Berlin." Whitney persisted. As it turned out, she was making final edits to a "Frontline" documentary about Pope John Paul II, for which Marritz had done much of the original photography. An important interview with German scholar and papal critic Hans Kung needed to be shot again. Kung had given his interview in English, but the European distributors of the film wanted their audience to hear it in German. Time was tight. Marritz was the man for the job -- if he would take it. Whitney had good reason to think he would: Kung lived in Berlin. "Before it came to my attention that the shoot was in Berlin, a place where I could rendezvous with Ilya, I was prepared to turn it down," says Marritz. But, of course, it didn't come to that, and in the end Marritz went to Berlin, Ilya saw his dad, and Whitney got her footage. Marritz spent four merrily frantic days in Berlin. "We booked a handsome, quiet reception room in the Hotel Adlon," he says. "I worked with my locally hired sound recordist, Simone, to make a handsome lighting set-up with a look consistent with the other interviews I'd shot for the show. The hotel provided a VCR and monitor so that I could show Kung a clip from his English-language interview. This prepared him to articulate the reply we needed from him in his native language. The shoot itself took about six hours, from pick-up of gear, load-in to hotel, light and prep, shoot and wrap." In the evenings, Marritz poked around the Potsdammer Platz and the Tiergarten with Ilya. "The shoot," Marritz says, "was extremely successful."

Scrapper In the beginning, Marritz wouldn't have dared to turn down work. It was too hard to come by. After graduating from New York's Hunter College in the early 1970s, Marritz drove a cab and bused tables at restaurants part-time while trying to break into the film business. He knew that he wouldn't find a full-time film job, that he would have to build his career one project at a time. To this day, Marritz says, "Very few staff jobs exist in the field. It's basically set up for teams to come together, execute jobs, then disband." He got an important break in 1974: "I was in Riverside Park throwing a Frisbee for our dog, Thor, and I met a film editor." The editor, Anitra Pivnik, was there with her dog, too, and she and Marritz got to talking. Pivnik said she was in film; Marritz said he wanted to be in film. Pivnik encouraged the neophyte. She told Marritz to get in touch with two men she knew -- Don Lenzer and Dick Pearce -- who had filmed the documentary "Woodstock" in 1969, and to use her name. Perhaps they'd have work for an up-and-comer. Naturally, Marritz took the cue. "I got sporadic work from both of them," he says. "I was green and relatively unschooled. I'd assist them on record company commercials, early versions of music videos, low-budget commercials and the occasional PBS documentary." In this fashion, Marritz earned his stripes, $85 a day, and a valuable lesson about career building. "Not all career advancement is attained through rational pursuit," he says. "Sometimes schmoozing is enough to open doors that one is not necessarily looking consciously to open."

Learning Curve Like all freelancers, especially those in the arts, Marritz had to build his own career. There was no traditional, clearly defined career path for him to follow, as there was for doctors and lawyers and teachers. He had studied film production in college, but knew that he would get the most valuable training on the job. So he took one small job after another, learning as much as he could from each project. Sometimes he was a gaffer, sometimes a grip, eventually a production assistant, and finally a camera assistant. He held microphones, set up lights, loaded film magazines into cameras, focused lenses. Getting more responsibility required "initiative, taking risks, an unbelievable capacity to persevere," Marritz says. "I've had to be many things." Part of the payoff has been a career of adventure spent with colorful people. In 1975 Marritz spent a week in New Mexico working as the camera assistant on a documentary about painter Georgia O'Keefe; shortly thereafter, he broke into the photographers' ranks as the assistant camera operator on a feature film called "Rockers," shot in seven weeks in Kingston, Jamaica. He has shot music videos for both Bananarama ("Cruel Summer") and fellow New Jersey native Bruce Springsteen ("Atlantic City"). He traveled to Illinois to film "Skokie," a feature film for television about neo-Nazi marches in that town, and to Bali, Australia, and Japan with dancer/choreographer Lori Anderson to film "Alive from Off Center." In the last year alone, projects have taken him to Mexico, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Spain. Working his way up from the bottom has given Marritz the confidence that he needs to do the good work that gets him jobs. "It took me a while to believe that I had innate skills of my own. Early on, I did as I was told and watched carefully, many days not fully understanding what was going on. Later, when I became a camera assistant on feature films, I stood closer to the chain of command, and I got a better idea of how decisions were made. I began to develop a voice -- an eye -- of my own." As Marritz developed technical expertise and an artistic sensibility, he also had to make decisions about the general direction of his career, decisions that would profoundly affect his lifestyle. If he wanted to pursue work in feature films, he would probably have to move to Los Angeles; if he wanted to establish a reputation among documentarists, he could stay in New York. He had worked on both feature films and documentaries, and could perhaps have gone either way. But he didn't want to move to California, and competition for jobs in feature film was extremely fierce everywhere. "I needed to make a decision," Marritz recalls, "and I said to myself, 'It doesn't look like it's going to happen for me in features, why don't I become the best documentary filmmaker I can become.'"

No Such Thing as a Sure Thing In this spirit Marritz plunged into a career that has rewarded him for twenty-five years with opportunities for travel, variety, and self-determination -- and which has sometimes perplexed him in its unpredictability. "I'm proud to be able to tell you that [another project is in the works]," he said last fall, "because if you ask me in February, I might not be able to tell you. It's not always a given. Often, when I've just completed a substantial project and I feel really poised -- nothing happens." |

||||||||||||||

|

February 14, 2000 Illustrator: Eli Cedrone Production: Keith Gendel |

We'd love to hear your comments about this article! Eric Gershon is Assistant Editor of 1099. | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||