|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

By Ken Gordon

|

You want to become a more perfect IP, right? Good for you. Maybe. For most IPs, a degree of perfectionism is essential for success. But some freelancers take this too far -- they insist on clutching onto their projects for one more day (or week, or month), forever futzing with the details. When the desire for perfection overwhelms all other considerations, causing them to minimize or ignore such important stuff as deadlines, budgets, and client egos, it becomes bad business. If you are a perfectionist, at least you can take comfort that you're not alone in your affliction: one of the greatest IPs of all time had the same problem. Believe it or not, Leonardo da Vinci had a bad dose of perfectionitis -- and his story is quite instructive. Leonardo: An Insanely Oversimplified Introduction

Leonardo was born in 1452 in an Italian village called (surprise!) Vinci. He came into the world a bastard -- the illegitimate son of a notary -- and then, by hard work and superhuman brilliance, transformed himself into perhaps the most accomplished IP ever. In spite of his genius, it took him years to achieve such mastery. Like all IPs, Leonardo first had to learn his craft; but unlike many freelancers, he wasn't formally educated in an academic setting. Instead, he went the apprentice route (the rough equivalent of a modern-day internship). At the age of 15 he was apprenticed by his father to a Florentine artist named Andrea del Verrochio. In Verrochio's workshop he learned the rudiments of painting, anatomy, and sculpture. Leonardo soon surpassed his master and walked out into the world in search of commissions. And that's when he really began his IP life. Field(s) Cows have fields but passions in motion are the privilege of the human mind. Some IPs spend a lifetime perfecting a single discipline. Not Leonardo; he liked to play the field. In fact, he wound up grazing all over the place: he was a painter, sculptor, scientist, engineer, architect, and inventor. And he didn't just try his hand at these tasks -- he mastered them all, which is why he's generally regarded as the quintessential Renaissance Man. The Clients of the Quattrocento IPs didn't have "clients" in 15th century Italy; they had patrons. These were enormously wealthy nobles who would commission this or that artist or architect or engineer to undertake projects. The purpose? The personal gratification or aggrandizement of the big cheese footing the bill.

At first, it was difficult for Leonardo to get patrons to pay him attention. He had, of course, tons of talent and miles of ambition, but as all IPs know, that's not enough to make you a success. At one point, Leonardo was what cliché-mongers call a starving artist. He had moved to Milan in search of fame and fortune and found himself living a very low-key sort of existence, subsisting on tiny pieces of consulting work, all the while trying to lob himself into the influential court of the Duke of Milan. To do so, he wrote a long letter to the Duke (who also went by the name of Ludovico Sforza) selling his talents as a military engineer. His marketing missive listed nine different wartime projects he would take on if given the chance. (Demonstrating an excellent feel for market forces, Leonardo seems to have divined that he would be more valuable as an engineer than as an artist.) But most interesting of all is the last section of the letter, in which Leonardo finally got around to his art. Listen to this: "I believe I am capable of giving you as much satisfaction as anyone, whether it be in architecture, for the construction of public or private buildings, or in bringing water from one place to another... I can sculpt in marble, bronze, or terracotta; while in painting, my work is the equal of anyone's." The letter eventually got through, and the Duke of Milan became one of Leonardo's biggest clients. (The gig ran for 17 years.) But there were many others, as well. Leonardo's patrons included Charles d'Amboise, Cesare Borgia, King Francis I of France, King Louis XII (France again), and Giulian de' Medici. These folks were as rich and powerful as Bill Gates and Ted Turner are today. They were the biggest, fattest clients in the Renaissance world and they all wanted Leonardo for themselves.

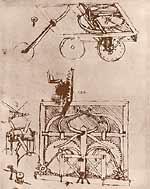

Well Done Takes Forever He labored much more by his word than in fact or by deed. Leonardo had a terrible time finishing his various projects -- many of which never got beyond the sketching stage. (Imagine a Web designer who was so brilliant that she never completed any of the pages she began, or an accountant who got so bogged down in the beauty of taking deductions that he never filed a tax form. How long do you suppose they'd stay in business?) Noted British art historian Kenneth Clark puts it succinctly: "Constitutional dilatoriness, an inability to carry anything through from beginning to end without the intervention of a thousand experiments and afterthoughts, had always been a part of Leonardo's character."

Why did Leonardo work for so long on his projects? We don't know for sure -- but we do know that some IPs tend to hold on to their work because they are insecure and afraid of criticism. Perhaps he thought that his patrons deserved only the best -- or, conversely, that they didn't deserve any consideration at all, and that they merely had to wait until Leonardo said he was through. Or perhaps it was just his voracious curiosity, always wanting to probe deeper into the nuances of a project. In any case, it's clearly not a good idea for any IP to allow his or her projects to drag on. Most clients will not overlook a freelancer's poor project-management skills. It Pays to Be Choosy Leonardo understood the importance of choosing the right gigs. For example, Isabella d'Este, Duchess of Mantua, was dying to get a portrait from him -- which might have been a juicy assignment, except that Isabella was a bit of a tyrant. She had a nasty habit of throwing artists who didn't work fast enough into her dungeon. And as Leonardo was in no hurry to finish any of his work -- and surely not a fan of dungeon life -- he ignored her numerous requests.

Leonardo biographer Robert Payne writes of Isbella d'Este's attempts to wring a portrait from him: "Nothing came of it; nothing could come of it; her importunity worked to her disadvantage. She had asked too often, too much." Would you want to work for a pesky client who could toss you in the slammer because you couldn't meet a deadline? Didn't think so. Projects (and Projectiles) You may be familiar with a little fresco called The Last Supper. And the painting called Mona Lisa (a.k.a. La Giaconda). Well, Leonardo also painted the Virgin on the Rocks and a couple of other works, known mainly to gals who majored in art history at Wellesley.

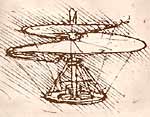

But there was one project that Leonardo was dying to attempt, and it wasn't a wimpy little commission for a portrait. It was a big bronze horse, which upon completion was to stand eighty feet high and weigh 20 tons. According to Robert Payne, it was "the one thing [Leonardo] wanted above all other things." Wisely, Leonardo's proposal to the Duke of Milan didn't emphasize aesthetics or Leonardo's desires -- it played straight to the client's ego: "I could undertake the work of the bronze horse, which will bring glory and eternal honor to the happy memory of the Prince your father and the illustrious house of Sforza." Leonardo got the gig, but never finished the job. The Duke of Sforza was booted out of Milan by invading French troops, effectively pulling the plug on the big horsey project -- and all other Sforza-sanctioned commissions. Though Leonardo's efforts did prove to be rather useful to a few people, at least: French archers used Leonardo's clay model of the horse for target practice. Lessons Learned From Leonardo Leonardo accomplished a lot but failed to complete most of his projects, and never achieved financial independence. The lesson, perhaps, is that brilliance and creativity are no substitutes for staying focused on the essence of a project. Allowing yourself to get distracted by interesting but peripheral thoughts is dangerous. On a broader scale, setting up huge numbers of endless projects that you couldn't possibly complete is not very smart. Actually, you're probably more efficient and client-oriented than Leonardo was. His failure to complete projects -- that is, to discipline his talent -- was a disservice to himself, his art, his patrons, and even his future admirers. And maybe this is the real lesson: do your work, do it well, and get it done. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

June 30, 2000 Primary Editor: Lawrence San Illustrator: Leonardo da Vinci Production: Fletcher Moore |

We'd love to hear your comments about this article! Ken Gordon is Associate Editor of 1099. If you like, we'd be happy to put you in touch with him, or channel you to any of the Great IPs in History. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||