|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

By Ron Miller

|

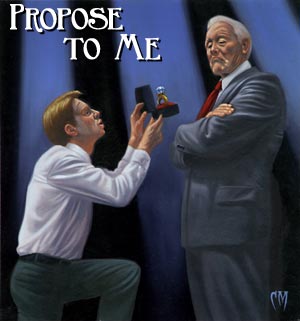

Referrals, word-of-mouth, cold calls, Web sites -- hell, even full-fledged advertising campaigns -- they're not the only ways IPs get business. Ever heard of RFPs? That stands for Request for Proposals. Yes, we know, it's not the sexiest topic in the world, but would you like to... how shall we put this delicately... earn more money? Yes? Now that we have your attention, let's talk about what RFPs are, where to find 'em, and how, when, and whether or not to mess with them as a way to get work. A Request for Proposal is a call for help by a prospective client -- a kind of formal S.O.S. by someone who needs to get something done. Actually, it's a solicitation of a plan to get that thing done -- and an opportunity for you, the capable IP, to explain why you're the right person for the job. Whatever your particular expertise, there's someone out there -- a company, a government agency, an individual -- who's willing to pay for your knowledge and skills, and one way for the two of you to feel each other out is the RFP process. What's in an RFP? Herman Holtz, author of How to Succeed as an Independent Consultant and about a zillion other books on consulting, notes that RFPs can vary drastically in length, scope, and degree of detail. Nevertheless, Holtz identifies four characteristics common to all RFPs:

Where Do They Come From? RFPs typically come from companies, government agencies, or nonprofit organizations. Each has its own needs and requirements, and these are reflected not only in the form of the RFPs, but in how they're distributed. While the government uses a standard set of forms and procedures, private companies follow their own idiosyncratic methods. The government is required by law to announce RFPs in a public forum, while private companies can limit the number of bidding invitations as they see fit. In most cases, the government must accept the lowest bid. A private-sector company may take into account many factors, such as price, the applicant's technical expertise, and how innovative the proposal is. Since many IPs will have little patience for the slow, dull, and boringly bureaucratic processes of government projects, let's leave aside government RFPs for the moment (you can read about them in the sidebar) and focus on the other major source of RFPs -- private-sector businesses. Corporations issue RFPs that call for all types of experts -- that is, people like you. Companies looking to outsource computer programming, network administration, Web design, Web hosting, and other IT functions often issue RFPs, as do companies looking for training and development or consulting services. Of course, unlike a government agency, the private sector is under no legal requirement to post RFPs in a particular place or handle them in any particular way. This may mean that the process is less bureaucratic than the government's, but it also means that the RFPs may be harder to find. Where Do You Find Them? It's up to you to make yourself known to the various companies that might solicit proposals. This means placing your name (or your company name) where clients looking for your skill can find it. If you develop training programs, for example, you should get your name listed in the American Society of Training and Development (ASTD) Buyer's Guide. RFP sources might find your name there and ask you to bid on a training project. If your profession has a similar guide or business listing service, you should be sure to place your name there. Your current clients may be another source of RFPs. If you've done good work for clients in the past, they'll be inclined to invite you to submit a proposal for a future project. Still another way to get RFPs is by word of mouth. In this instance, a client likes your work and tells a colleague about you. The colleague then invites you to submit a proposal based on this recommendation. Outside the RFP Process Of course, not all requests for proposals are issued as formal RFPs. You might get invited to make a proposal based on a conversation with a client, and only later be asked to formalize it in writing. In this case, you're probably not competing for the project, but rather writing up a plan that has at least tacit approval in advance. Your chances of landing such a job are pretty good. Not all jobs are conducive to the RFP process in the first place. If you're a freelance restaurant critic, you probably won't be asked to cook up many proposals; sending in some published clips will probably be enough for a food editor to decide if you're right for his menu. Similarly, actors appear at auditions and musicians send in tapes; they rarely propose. There are also freelance professions where proposals aren't the norm but may be part of the mix. For example, graphic designers usually just show their portfolios, but may be asked for proposals for expensive, ill-defined projects such as Web sites. Truth is, there are many situations where you'd be hard-pressed to say whether a prospective client's request was an "RFP" or not; and where they'd be hard-pressed to say whether your response was a "proposal." Unless you're bidding on a government project, where the rules are stricter, don't spend much time worrying about such questions. Don't ask the client, "Is this an RFP?" The question sounds unsophisticated, and the short answer usually is: it doesn't matter. What does matter is the competitive reality of each individual situation, and your skill (core skills plus sales psychology) in landing the client. Is it Worth Your Time and Energy to Respond? So let's say you're staring at an honest-to-goodness RFP. What next? First you need to decide if writing a proposal is worth the investment of your time and effort, because there's always the risk that you won't get the project. IPs in engineering, architecture, and many computer-related professions usually have no choice in the matter -- they work on large, expensive projects where a formal proposal is standard procedure. However, for most professionals, responding to RFPs is only one of the options among the overall marketing choices available to them. Some IPs refuse to participate in the RFP process at all, saying it's exploitative. One such refuser is E.J. Brennan, a freelance computer programmer operating in Goshen, Mass. "In general," he says, "if someone asks for a detailed RFP, I look for another project." Brennan reasons that someone who asks for a proposal on speculation is usually trying to get something for nothing -- a brain-dump. The exception to Brennan's policy involves cash: he will respond to an RFP if he gets paid for it. RFPs are a type of project for him, not simply a tool for getting projects. "Any RFP that is detailed enough to actually mean something, should be work that is paid for," he says. "Any RFP that you don't mind doing for free is so trivial that it's not worth it." Whether or not you could operate as Brennan does will depend, among other things, on the conventions of your profession and the state of the economy. Brennan concedes that part of the reason he's able to operate as he does is the abundance of work available right now, combined with a scarcity of programmers. He's in a strong position and knows he'll get work regardless of whether or not he bothers with RFPs. How to Be Responsive If you decide that responding to RFPs will be part of your marketing strategy, you should develop a response procedure to minimize the time you take away from paying work. You could, for example, devise a template that includes the information common to most proposals. Or you could use computer software designed for composing proposals (see Additional Resources for more information on these packages). Whatever your method, once you commit to responding to an RFP, you need to familiarize yourself with the details of the source's stated problem, which might be a task in itself. "Nobody gets all the meaning on the first reading," says Holtz. "Be prepared to study it." (Studying it may not be enough. Clients don't always know exactly what they want, in which case your best strategy may be to tell them what they should want.) Once you understand what's being asked of you, Holtz suggests preparing a flowchart that shows what needs to be done and how you would complete the necessary tasks. This will lend some definition to the process and provide you with a plan of action. When you're ready to draft the actual proposal, you'll also have an outline ready. Most IPs have some sort of standard proposal format. Former IP Web designer Andrew Kesin, of Northampton, Mass., outlines his projects in phases, describing the specific tasks he expects to complete within each phase. In the first phase, for example, he might try to define the scope of the project, which requires research; in the second phase he might design a site map; and in the third phase, he might build a prototype of a site. He adds phases as necessary, until the job is complete. He always attaches dates to the phases. Phasing breaks down the project into a series of manageable tasks and provides milestones for each project element, which are also convenient for billing purposes. Holtz suggests breaking a proposal into five sections, as shown below. (He recommends using specific titles in place of these generic titles to give the proposal more authority and make it stand out from competing proposals.)

Most proposals also include a cover letter. Holtz recommends writing an "executive summary" of no more than two pages, a document tailored to the suit who's too busy golfing to read the entire proposal. In this type of letter, you should include the price, an outline of your plans and expertise, and assurances that the client will be getting your best efforts. Naturally, Holtz recommends using the letter as yet another opportunity to sell the proposal. By contrast, Kesin merely includes a simple cover letter indicating that he has enclosed the RFP. IPs need to balance their time between performing work that will pay and looking for new projects -- also known as marketing. RFPs are typically just a part of that marketing effort, so how much time should you be spending on them? Opinions vary. Holtz suggests spending a third of your time on marketing overall. ("If you wait to be not busy to market yourself, you won't have work," he points out.) Kesin estimates that when he was an IP he spent between 10 and 20 percent of his time responding to proposals. Brennan, the computer programmer, says he tries to spend no more than four hours getting any new project. Proposals, Contracts, and Sales Even if you're not responding to a formal RFP, being familiar with proposals can be helpful. For example, you might consider defining the parameters of all your projects in something like a proposal format. This can protect you and your client by setting expectations for each party. Speaking of protection, a proposal (formal or not) can form the basis for a contract that you draft after the proposal is approved. (Having a contract, by the way, is usually a good idea, except on the smallest jobs.) In fact, sometimes the only real difference between a proposal and a brief, informal contract is that the contract gets signed and dated by both parties. More often, the contract goes into more detail than the proposal did, especially about issues like payment terms; and it may also specify scary stuff like penalties for non-performance by the IP or non-payment by the client. Writing proposals usually requires a substantial investment of your time. If you're going to do it at all, you might as well take the time to do it right. You need to differentiate yourself from the competition -- or, as Holtz says, "you need to be bold enough to promote new ideas." Do something the other guy hasn't thought of, or isn't taking the care to do. There's no second place when submitting a proposal -- only one winner and a bunch of losers. Make your proposal stand out, and never forget that drafting and submitting a proposal isn't really about the formalities. It is, ultimately, an act of salesmanship.

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

July 24, 2000 Illustrator: Craig Maher Production: Fletcher Moore |

We'd love to hear your comments about this article! Ron Miller is a freelance writer who lives in Amherst, Mass. If you like, we'd be happy to put you in touch with him, or with any of the other IPs named in this article. |

||||

|

|

|||||