|

Boxing

is "the water-cooler thing" in O'Brien's life. "Boxing offers me

a moment so intense that I don't have to think about all my professional

pressures."

|

|

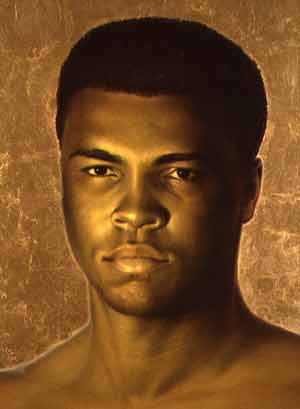

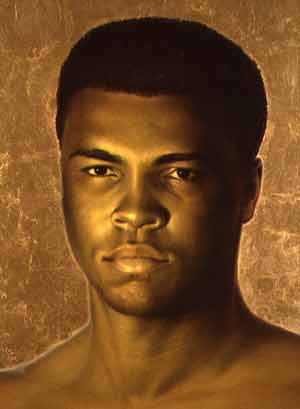

The Worker

"When the timelines were a little longer, all the illustrators did what I do," says O'Brien. "Now, to get it done quickly, a lot of magazine illustration is looser, more exaggerated, a more cartoon-based style. But I'm the most realistic illustrator in magazines, and I'm able to do it on a short deadline."

O'Brien's is a solitary line of work and, like many IPs, he considers his privacy both a blessing and a burden.

"Sometimes input from the art director makes my job easier," he says, but "mostly I enjoy them giving me the job and approving my sketches and staying out of it." The art directors he knows best (including his wife, art director for young adult books at Scholastic, Inc. in New York) generally leave him alone. Entire weeks go by when O'Brien doesn't meet with anyone for professional reasons. Usually, he doesn't even deliver the finished product in person. "I have it delivered," he says.

Boxing is "the water-cooler thing" in O'Brien's life. "Boxing

offers me a moment so intense that I don't have to think about

all my professional pressures. And it's so completely different

-- a different part of my brain. My work is so sedentary."

Professional Pressures

Tim O'Brien was recently on his way to a speaking engagement at New York's School of Visual Arts when his cell-phone rang. It was Ken Smith, assistant art director at Time magazine. Smith, who often calls on O'Brien for rush jobs, wanted a drawing -- not a cover, which usually takes three days, but an inside illustration, smaller and less detailed than a cover -- and he needed it in a day.

"When the phone rings, the second that I'm pitched the job, I already start to work on ideas in my head," O'Brien says. "The first things that come to you are the bad scenarios of how it could go."

Smith wanted to illustrate the end of billboard advertising for the tobacco industry -- part of a giant agreement to resolve state claims over health costs related to smoking. O'Brien knew that the illustration would depict the Marlboro Man, but feared that it would be something cliche or obvious. Concern that he would be asked to paint the famous cigarette cowboy in the unemployment line or riding off into the sunset simmered and stewed in the back of his mind throughout the lecture.

After the ceremony, O'Brien went directly to Smith's office, where they worked on an illustration concept -- an advertising icon, a billboard, a sign of changing times. O'Brien had brought his camera and Smith, who has a rugged look, posed for the familiar figure of the ubiquitous Marlboro Man. O'Brien did a sketch of some workers painting over a picture of the Marlboro Man and got approval while still in the Time office.

Back in a room on the third floor of his Park Slope brownstone (where he tacks outstanding vintage magazine covers on a bulletin board for inspiration) O'Brien started working at midnight. The third floor lights burned all night long as he thrashed about in a knock-down, drag-out fight with the clock. He finished in the twilight of the next evening, after 19 straight hours of work.

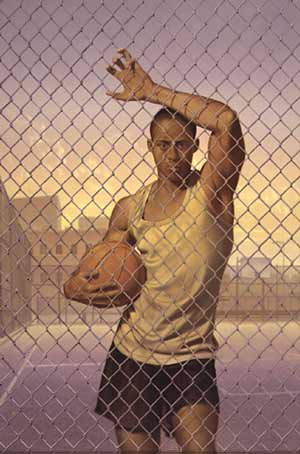

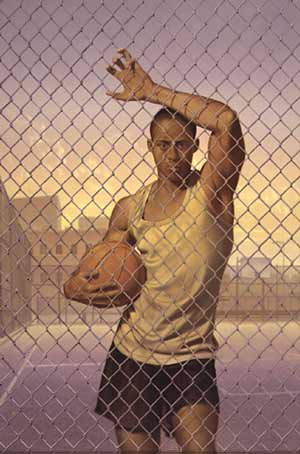

Out of the Studio, Into the Ring

What better way to relax after such a punishing ordeal than to pack up the gear and drive over to the YMCA to dodge left hooks and right crosses? Going to the Y has its social aspects, but mostly O'Brien goes there to box. "Among my [professional] peers I don't mind the competition of egos, but when it comes to going to the gym, I don't want to always be the center of attention," he says. He was exactly that for a while earlier this year, after The New York Times did a piece about him. "I'm no celebrity, so it was fun," he admits. "And when I think about the kinds of work other people do, I feel blessed."

Boxing suits his freelancer style, too. "I tried team sports, but found them frustrating," he says. "Boxing suited my personality. If I did poorly no one was upset, and if I did well, it was all me."

Although he's doing well now, O'Brien keeps in mind how hard it was to get started, and worries that if the art directors he works with should be replaced, he'd probably have to start over, establishing new relationships with new people. "At the beginning," he recalled, "there was a lot of groveling." He found an agent and advertised himself. The agent still handles his business affairs, though most of O'Brien's assignments come to him directly. He also still advertises in such annuals as American Illustration Showcase and enters juried competitions. Taking a prize in a show, he says, is "actually the best advertising."

|

|

The best thing about success is the freedom to choose his assignments, to turn down projects that don't speak to his heart, to take the fun jobs.

|

|

For O'Brien, the best thing about success is the freedom to choose his assignments, to turn down projects that don't speak to his heart, to take "the fun jobs." Magazine covers are rewarding because they're conspicuous and ubiquitous, an ego boost because "everybody sees them." Book illustrations are also worth the pains because the product lasts longer and the art directors often welcome suggestions.

"I've made less money than I could have all through my career," O'Brien says. "I've turned jobs down that weren't good fits. And I think I've been rewarded for it, because I sought this market out and developed a style."

Ultimately, it's the excitement, the challenge, the race with the clock that keeps O'Brien electrified from dusk to dawn to dusk again. "It's hard to get that adrenaline pumping when you're doing something for Washing Machine Monthly," he points out. Then, after a thoughtful pause, he admits: " I still take some jobs for the money."

|