|

|

||||||||||||

|

About San

inSANity columns: The

Better You Are, When

The Bastards Ugly Brides and Other Temptations Will The Real Freaks Please Raise Their Hands? The Fine Art of Kicking Yourself |

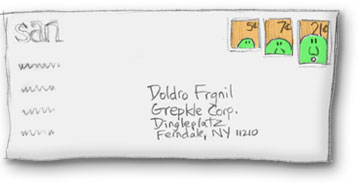

Putting Your Stamp On ItThis morning I got a brochure in the mail trying to sell me a "personal postage meter." Part of the pitch is that a micro-business will present a more "professional" appearance sending out metered mail rather than stamped mail. The implication is that an independent professional would be better off looking a little less independent professional-ish. I've gotten ads like this in the mail before, and once, when I was renting a small office for my solo writing/graphic design/illustration business, a salesman walked in and tried to sell me one of these personal postage meters. Picture this poor guy in his polyester suit, looking around uneasily at the weird cartoon drawings and brochure layouts taped to the walls of my office, trying to figure out what the hell business I was in. (The calligraphically hand-lettered sign stuck to the door, "Lawrence San Studio," wasn't very descriptive.) I'm afraid I was pretty relaxed with him -- "relaxed" being a bit of a euphemism. I was in my own office, after all, and he was an uninvited salesman, and... well, what can I say, it had been a long day. I leaned back in my chair and put my feet up on the desk, while he stood there awkwardly displaying an actual postage meter in his outstretched hands. "With this meter," he said, "your mail will look more professional--" "Look more professional to whom?" I asked. "Mostly I mail checks to vendors." "Well, it will look more professional to them," he said. "Do you think if my mail looked amateurish they wouldn't cash my checks? That would be a good thing, actually." "Uh, no, but... But you must also send invoices to your clients!" He was triumphant with the logic of his argument, but then he looked around my somewhat unusual office and his voice became a shade less certain. "Don't you?" I admitted that I did. "Well then. If your invoice envelopes were metered, they'd look more professional," he said. "More like a real company sent them." "Why do you assume," I countered, "that looking professional and looking like a 'real company' is the same thing? I think it's two different things. By the way, would you like to sit down?" He gazed in some confusion at the only two guest chairs in my office. They were piled high with stacks of paperwork, felt markers, crushed styrofoam coffee cups, tubes of watercolor paint, a half-eaten sandwich, floppy disks, an inflatable plastic dinosaur, and other miscellaneous debris. "Yes, thank you, but... I don't see anywhere to sit..." I shrugged. "What you're selling is irrational," I said. "It makes no sense." "Why?" "The appearance of my mail to vendors is irrelevant; if I pay them on time, they're happy. Of course how my mail looks to my clients is important -- after all, among other things I'm a graphic designer -- so look at this." I held up a blank sheet of my carefully designed, meticulously printed stationery. Then I showed him an outgoing invoice waiting to be mailed. Instead of the typical single postage stamp, it had three smaller-denomination stamps that added up to the correct postage. They were not the standard American flag stamps. They were three different stamps I had carefully chosen for graphic appeal, and carefully arranged to have both a conceptual and a color-scheme relationship to each other.

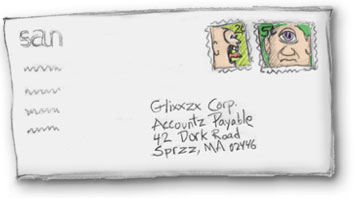

"That's nice," he conceded, "but it must be so time-consuming to do that." "I enjoy it. Anyway this is a small business; I only send one or two invoices a week, tops," I said. "It only takes an extra few minutes to arrange the stamps that way, and my clients remember it. Sometimes they even comment about it. Figuring out the conceptual relationship between the different stamps is like a little puzzle -- some of them even look forward to it when they get my invoice. Sometimes they call to see if they got it right. It's also a reminder to them of how graphically creative and thoughtful and meticulous I am, which is part of what they pay me for." I suspect he was starting to realize that I had actually given real thought to this postage thing, that I wasn't just reacting off the top of my head to the fact that a postage guy happened to walk in the door. He was probably used to objections based on price, but not to this. In effect, I was attacking the core value proposition of his business, which was selling "personal" postage meters to people like me. He wasn't going to give up easily. "Forget about invoices," he said. "You already have those clients. And you're an art guy so you like to fuss with stamps, how they look on an envelope. What about marketing pieces you send out? You send out hundreds of pieces at a time, don't you? You're going to fuss with the stamps on all of them?" "Why would I send out hundreds of marketing pieces at a time? If I were content with the typical 1 or 2% response rate of a direct-mail campaign, I'd have to send out thousands of pieces, not hundreds. What do I look like to you, General Motors?" (One of my favorite rhetorical phrases.) "My marketing is targeted. I mean really targeted. I research a few potential clients. I know the individuals' names, what they do, maybe even what projects they're working on right now. I know who's competing with me for each project. Maybe I don't use the mail at all, since the phone is faster, but maybe I do write to them. A few people at a time. Not stacks of mail." "Well," he said, repeating what was probably his standard trump card, "don't you want to look like a real company?" "Hell, no," I said. "I want to look like a real person -- that beats a real company any day." I painted him a word picture of a potential client, sitting in an office with stacks of unopened mail, a daily chore. A pile of similar envelopes, each with the same kind of metered postage in the upper right. And the recipient's address machine-printed on them. "Listen," I said. "Maybe out of all those envelopes, just one of them would have the recipient's name and address hand-printed by someone, scrawled in ink right on the envelope. And with a postage stamp stuck -- not fussily, let's say just stuck messily -- in the corner, which envelope do you think he would open first?" "The one with the stamps," he conceded. "Sure," I said, "because it looks like it might be personal mail, not part of a bulk mailing. In fact manufacturers are inventing all kinds of ways to make phony "hand-printed" labels come out of machines. And direct mailers pay extra to avoid metered postage; they put bulk-mail stamps on their envelopes that might -- at first glance -- be mistaken for regular stamps." The expression on his face made clear that he already knew all this postage-psychology stuff, so I continued in a slightly more philosophical vein. "I can't compete with 'real companies,' as you call them, on their own terms -- I don't have a sales force or elaborate customer service or the efficiencies of scale that they have. I have to compete on my own terms: I'm a person, selling to another person. My mail stands out and gets opened precisely because it looks like a person did it. My bigger competitors can't do that because they have to send too much mail. So why should I throw away one of the few advantages that my small size gives me? Uh...do you have anything else to sell me?" He rewarded me with a sour look and left my office, still clutching his "personal" postage meter.

Let the world know you as you are, not as you think you should be, because sooner or later, if you are posing, you will forget the pose, and then where are you? The whole episode got me to thinking, and not just about mail. True, as a writer and graphic artist I was obviously selling a highly customized service, one where individuality could be perceived as a virtue. But what if I'd been selling a service more "corporate" than writing and art -- for example, if I'd been an independent management consultant? Then would I have been better off projecting a "real company" image? Or what if I'd been trying to sell my services to a highly bureaucratized institution that was reluctant to deal with individual freelancers, or even had a policy against it? The implications of this question extend far beyond postage meters. For example, the name of your business can make it sound like a person (you) or like a "real company." Even something as subtle as whether you refer to your business as "I" or "we" affects your image. More than that... your mentality affects it. And you project it. I suppose if you're more an entrepreneur than a "pure" independent professional -- that is, if your real goal is to build a company, not a personal brand -- then the answer is self-evident: try to look bigger than you are. But if you're building a brand that's essentially yourself, and you work alone, any prospective client is going to find out soon enough that you work alone, before they sign a contract. If they're going to rule you out on that basis, fine (actually, I don't mean fine, I mean screw 'em) but then fooling them on the first impression wouldn't help in the long run anyway. Besides, doesn't everybody know that only people do things, that companies and other institutions are mere abstractions? You don't even have to wait for the widely predicted trend -- i.e., that the Internet will "disintermediate" many corporations and replace them with "virtual companies." The truth is that all companies always were virtual, just a temporary and shifting pattern of people. Even "fixed" assets like machinery break down and rust unless people constantly maintain them. Ultimately, companies don't exist. People exist. True, the prejudice against doing business with individuals does have some logic to it (I'll deal with that in another essay), but there are just as many arguments for working with individuals. Overall, the anti-independent professional bias is a historically temporary aberration that will inevitably fade away as companies become even more abstract than before, and more workers go out on their own. But why wait? Small is beautiful; come out of the closet. Be proud of your postage stamps. |

|

San was the founding editor of 1099 Magazine, serving as its first editor-in-chief and creative director. He's now back in the boss-free world as a freelance writer and illustrator. In addition to the inSANity column on 1099, San's other writings and cartoons are at www.sanstudio.com. We'd love to hear your feedback about this column. |

|

|

|

|

The 1099 name and logo are trademarks of 1099 Magazine.